We use cookies to make your experience better. To comply with the new e-Privacy directive, we need to ask for your consent to set the cookies. Learn more.

Seydou Keïta

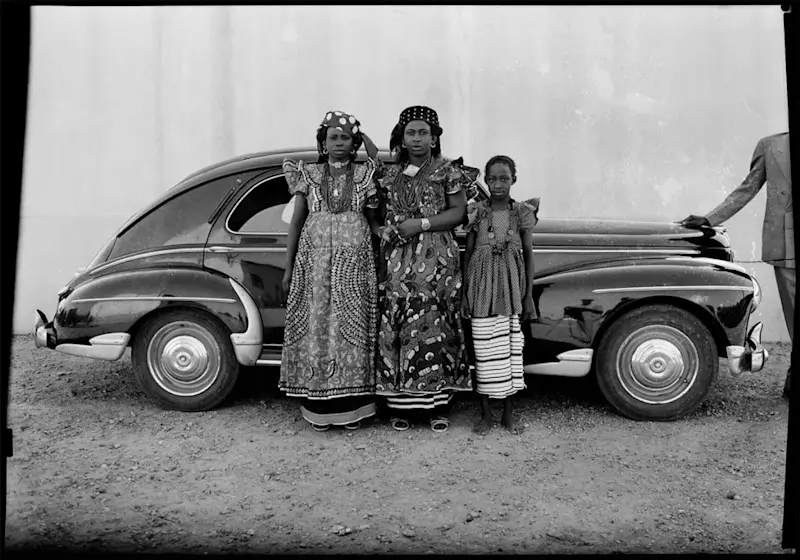

May 21. On this day in 1954 Seydou Keïta photographed three women in front of his car in Bamako, French Sudan.

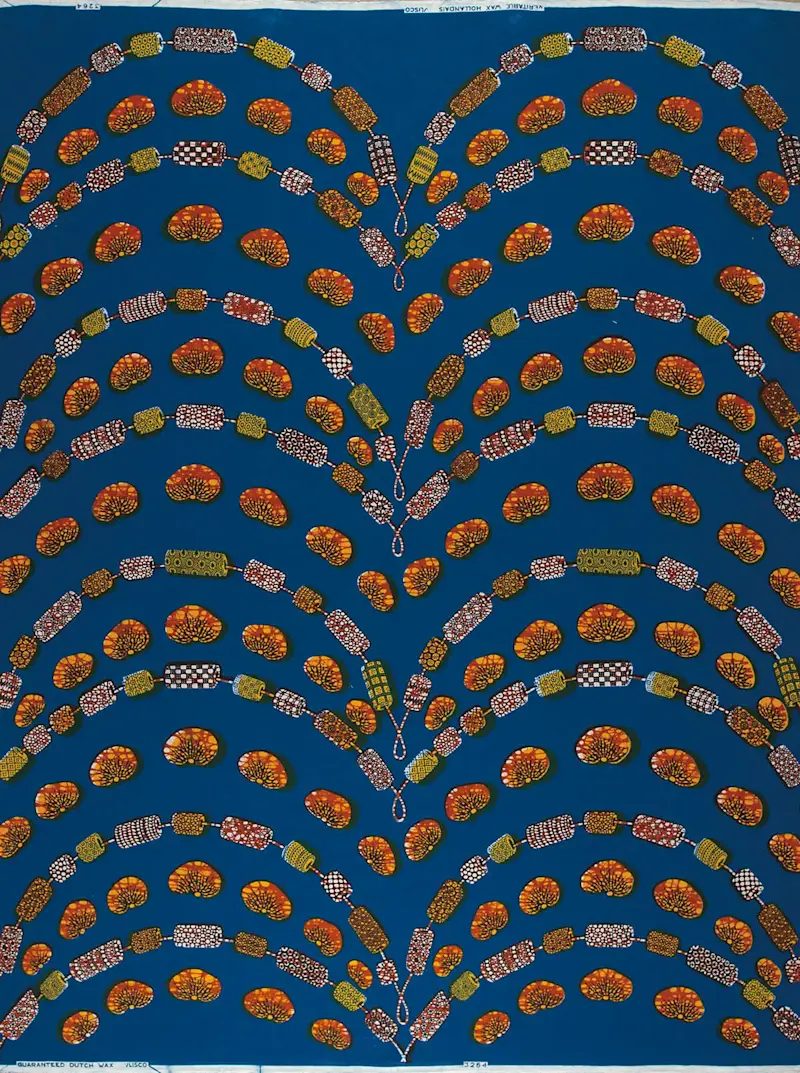

In the reflection of the Peugeot’s fender you can see Seydou Keïta and his tripod as he eternalizes two adult women, a barefoot child and the arm of a man. The woman in the middle wears the 1950’s Vlisco dessin 14-0792. It is named ‘Tomato’, ‘Necklace’ or ‘Aklepan’, depending on which country you are in. After some small adjustments in 1977, the wax-print was marked 14-3264.

Seydou Keïta. Untitled, MA.KE.064: 1954. Modern gelatin silver print. Courtsey CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection © Seydou Keïta/SKPEAC.

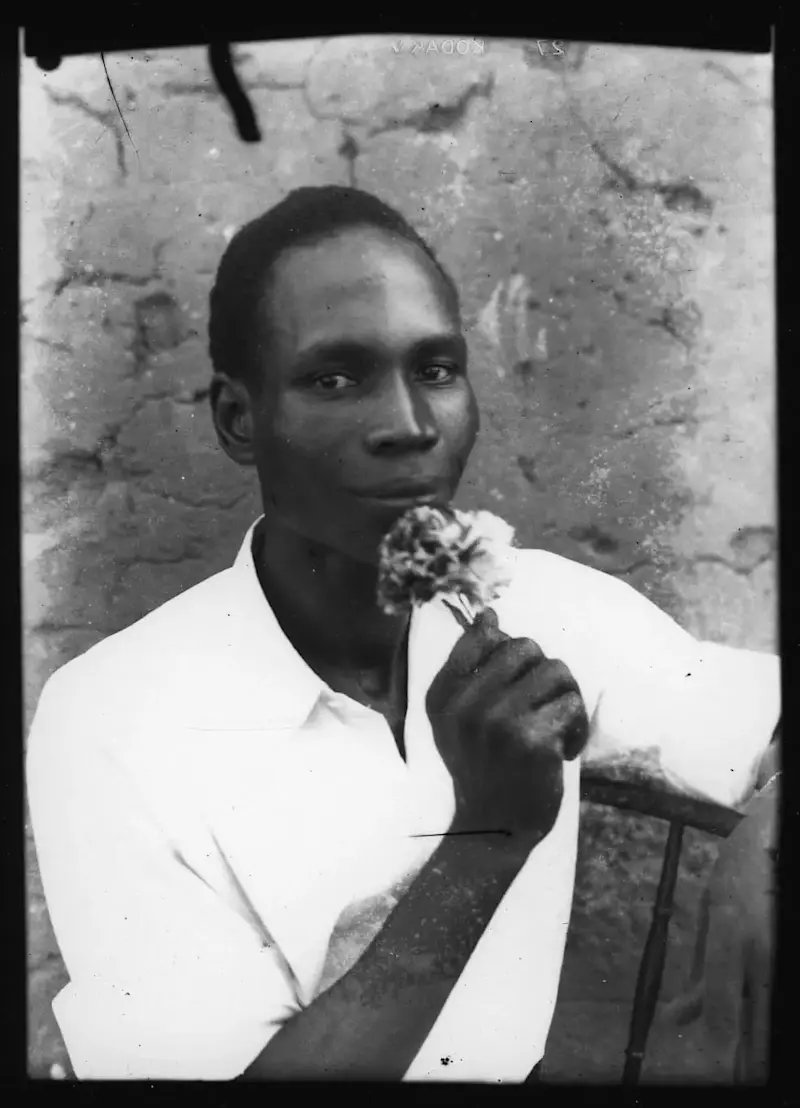

Kodak Brownie Flash

There are many documents that render the lengthy and unique connection between Vlisco and Africa, however, only a few old photos actually visualize it. One of the African photographers that captured the Vlisco-Africa connection is Seydou Keïta, who once begged his uncle to give him his Kodak Brownie Flash. When Tièmòkò handed over the cardboard box camera to his nephew, the 14-year old Seydou instantly knew he wanted to be a photographer, although he still worked as a carpenter for the next ten years. But in 1948 Seydou could name himself a photographer after he opened his own photo studio in Bamako-Coura, La Nouvelle Bamako, right across the prison. ‘It was a place where no one ever wanted to live because of the “spirits” who were throwing stones in the night. Even today, if you sleep in this house with the lights switched off, the immaculate great white spirit-horse might appear. We often hear it pass by at triple gallop and see it shining in a bright light. But it was never a problem for me, as photography always requires lights to be on.’

A place to talk

In 1908, Bamako became the capital of French Sudan. The city was under colonial rule from 1880 till June 20, 1960. A few months later it became the capital of the Republic of Mali. When Seydou opened his studio, there were no more than 100.000 people living in Bamako, but the city was a crossroad where Ivorians, Burkinabes and Nigerians stopped over en route to Dakar. His studio also became a meeting point, a place to talk for the inhabitants of Bamako. ‘All citizens of Bamako came to have their pictures taken by me. Especially on Saturdays, they came in by the dozens.’ Even President Modiba Keïta visited, saying ‘Anyone who hasn’t had his picture taken by Seydou Keïta does not have a picture’.

40 photos a day

All photos were stamped on the backside in red or black ink, marking the official Seydou Keïta photo – and the date of origin. It was called a card and in the 1950s the price was 300 Francs for daylight pictures and 400 Francs for studio lights – due to the cost of electricity. Seydou took around 40 photos a day and (most of the time) took only one frame of each sitting – also due to the costs. Seydou enjoyed his work and made a good living out of it: he supported three families and was able to buy a Peugeot 203 in 1952, Peugeot’s first new model after the Second World War.

A civil servant

In 1962, two years after Mali gained independence, Seydou Keïta was forced to close down his studio. The socialist regime that came into power wanted him to work for them as a photographer. ‘They made it clear to me that I was the only photographer who could work for the state.’ So for the next fifteen years, Seydou was a civil servant until his retirement in 1977. After that he abandoned photography, and went to the mosque and fixed cars instead.

Seydou Keïta. Untitled, neg. 00975: 1949. Modern gelatin silver print. Courtsey CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection © Seydou Keïta/SKPEAC.

Enchanting portraits

Seydou Keïta created a vast collection of stunning photos, portraits of all kinds of people living or travelling in a transitioning country, as French Sudan became Mali. Government officials, policemen, military, dandies, musicians, schoolkids, youth, mothers with children, newlyweds, elderly people and babies; everyone was seated in front of Seydou’s camera in La Nouvelle Bamako. The portraits are enchanting, also because the photos contain many interesting characteristics and details. We know that Seydou offered his customers accessories such as watches, pens, necklaces, plastic flowers, a radio set, telephone, alarm clock and his own Vespa and Peugeot 203. So when you look closely, you’ll recognise the same props in different photos.

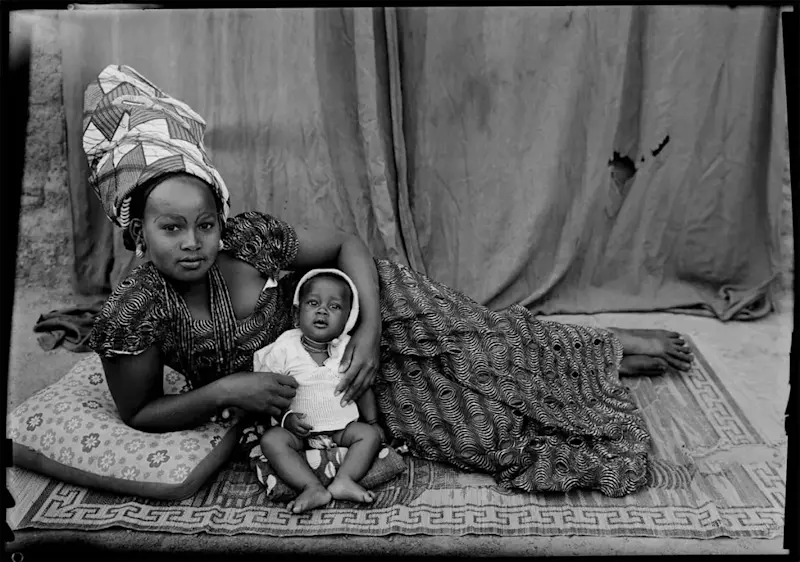

Backdrop

Another extraordinary detail is the backdrops Seydou used, such as his own fringed bedspread that functioned as a backdrop between 1948 and 1954. ‘Sometimes, printed backdrops went really well with the clothes my customers wore, especially for women.’ Men in certain official positions dressed the European way, but for women, clothing stayed traditional in that time. ‘Western garments such as skirts only appeared in the late 60s. Women came wearing their long dresses.’ Almost all women Seydou photographed, are wearing fabrics, like Vlisco wax-prints.

Seydou Keïta. Untitled, MA.KE.308: 1952-1955. Modern gelatin silver print. Courtsey CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection © Seydou Keïta/SKPEAC.

The eye of my rival | Moran’s eye

The eye of my rival

H-516 is the most-seen Vlisco-dessin in Seydou’s photographs. It is also known as ‘The eye of my rival’ or ‘Moran’s Eyes’. Designed by Bert Visser 1949, H-516 became a beloved back then – and still is very populair today. Like ‘Tomato’, ‘The eye of my rival’ was also sold in Togo and Congo in the 1950s, many thousands of kilometres away from Mali. These Vlisco fabrics ended up in Bamako by domestic trade, as Bamako was an important stop on divers trade routes, like the chemin de fer de Dakar au Niger (the railway line between Dakar and Koulikoro).

Formidable figure

Seydou Keïta’s photos made their first international appearance in 1991 and have been celebrated from New York to Tokyo ever since. After Seydou died in November 2001, The New York Times named him ‘a formidable figure in photography’ and praised the pattern-on-pattern look as his signature style of portraiture. Nowadays there is something ironic about Seydou’s work: despite his many efforts to keep his photo’s affordable, the photos are ranging up to 60.000 euro a piece anno 2017.

Note

Seydou Keïta filed over 15.000 photos and you can use the background as a reference to date the year the photo was taken. In the period 1948-1954 he used his own fringed bedspread, in 1952-1955 a dark grey curtain, in 1954-1955 a cloth with small flowers printed on it, in 1954 he also occasionally used a black and white plaid cloth, in 1956 a cloth with a leaf pattern, in 1956-1957 an arabesque pattern and between 1957-1961 a dark, grey, neutral-looking curtain. What happened with the photos he took for the Malian government remains a mystery.